When I was 17 and Peter was 21 in 1980, we visited Herbert Falk’s family in Algonquin, Illinois, which is a suburb of Chicago. We were very curious about this country we knew from television. We spent three awesome weeks there. Our families were connected with the friendship of Herbert Falk’s aunt Bertha Oestreicher and my step-grandmother Emma Willhauck-Weickgennant, who maintained their friendship through correspondence throughout the years.

Decades after his escape from the Nazi regime, Herbert and his wife Claire visited his childhood home in Germany in 1982. Perhaps this trip raised memories for him; the last goodbye with his father, who had remained in Germany and was killed in a concentration camp, or the memory of his mother Karolina Falk, who died when Herbert was only 5 years old. A physical place for paternal remembrance does not exist yet, but a gravesite for Herbert’s mother exists for commemoration and mourning. It is located in the Jewish cemetery where she was buried in 1936.

During their first visit in Bad Mingolsheim, Herbert and Claire were visitors in the house of my grandfather Josef Willhauck, who was the mayor of the village at that time, along with his wife Emma Willhauck-Weickgenannt. Since my father Ernst Willhauck was a classmate of Herbert, our family was invited. Our families has had other encounters since then. From time to time Herbert and his wife were drawn back to his old roots. They would have liked to return once again, however the journey would be too difficult for them due to their ages.

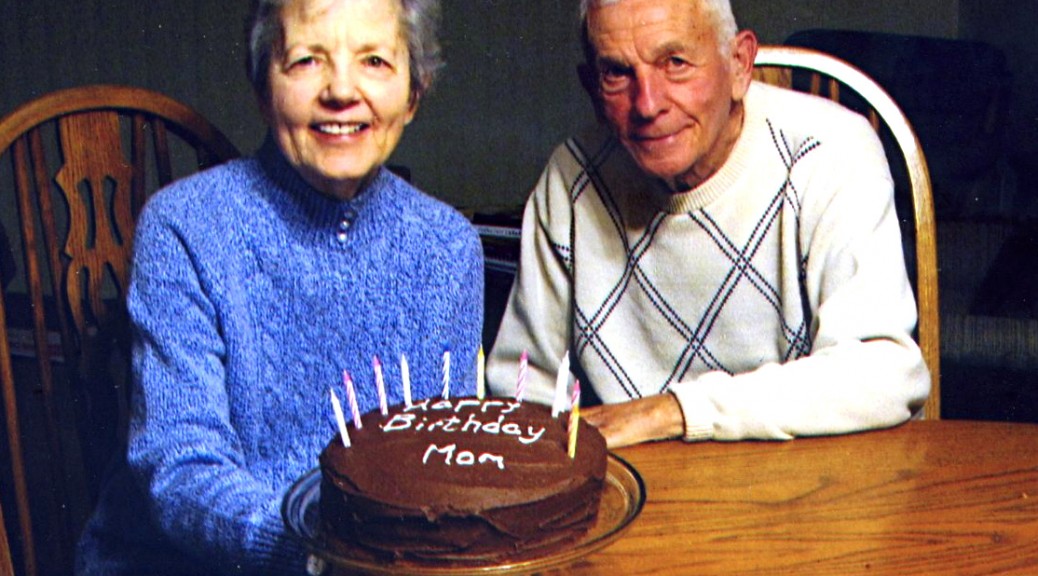

In 2016 Herbert celebrated his 85th birthday. He celebrated 6 birthdays in Bad Mingolsheim and 78 in the USA. It is quite interesting to realize how important geographical roots are despite the fact that people grow up abroad and then get settled and integrated in foreign societies far away from the original home.

On the occasion of Herbert’s 85th birthday we again traveled to Algonquin after 26 years to visit Herbert and his family. This time Peter and I brought my daughter Nora. When we turned into their driveway, we were tense and curious at the same time. How will it be? When Claire opened the door, we suddenly knew we had arrived again. There was that old sense of confidence, the awesome hospitality and the hearty openness.

In the course of our daily visits lots of memories were brought back on both sides, shared and exchanged. Herbert remembered the passage with his grandmother Betty and his Uncle Max on the MS Europa. He remembers leaving his father, the familiar environment – maybe with the feeling of a last good-bye, maybe not – not completely aware about the personal danger and the motivation to leave the only home he’d ever known. He had already suffered verbal and physical assaults from teachers and classmates. They sailed to a new home away from home, hopeful, anxious and curious. Just before the arrival in New York came the first shock: Herbert was ill, suffering from tonsillitis. They were transferred to a quarantine camp upon arrival. Finally the doctor released them with the words, “The boy is okay,” so they could get off the ship and proceed with the immigration formalities. According to the Immigration Act from 1924 there was a quota defining how many immigrants per nationality and year were allowed. The newcomers had to queue in lines and were extremely controlled. Herbert still remembers that the heels of the shoes were cut with sharp knives by the American police in order to control the illegal import of high amounts of foreign currency.

Herbert, his grandmother and uncle had left Germany because they were threatened for being Jewish. They had headed to a country where they had indeed been saved but were welcomed with restrictions. Immigrants were allowed to bring personal items with them, which were transported in containers. From this ship’s passage there still exists an antique armchair that is in Herbert’s living room. The armchair was originally in the house of Herbert’s grandfather Moritz. This heirloom is cherished and serves less as a seating accommodation but more as an emotional bridge to the happy days of Herbert’s childhood spent at his grandparents’ house.

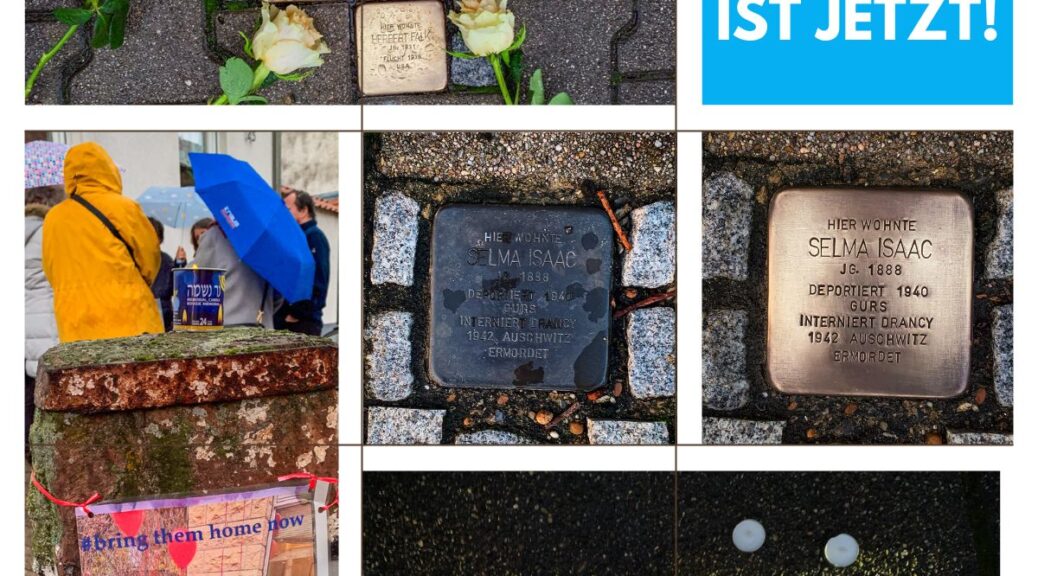

The trip down memory lane was touching for us, not only because of the role my grandfather had as a political figure in our village during the Nazi regime, but also for Herbert and his family, who learned a lot about the destiny of the family members who stayed in Germany. This is due to the tireless research of databases by the “AG Stumble Stones,” who could enlighten the personal family history. Germany has never paid a financial compensation to the Falk family; however an honorable remembrance for Herbert’s father Julius Falk was now initiated. Julius was transported to Gurs and killed in the concentration camp. Herbert Falk very much appreciates and supports the “stumble stone” initiative as a sign of commemoration in front of the house where he lived.