Julius Falk was born on July 10th 1898 in Östringen. His father, Louis (Ludwig) Falk, was from Malsch but he moved to Östringen when he married Babette Wolf who came from there. Julius grew up there with his elder sisters, Elsa and Hilde and younger brother Berthold.

During the First World War, Julius served with the 110th Infantry Regiment, which was based in Heidelberg. On September 8th 1917 he was captured by the French near Verdun and taken to a prisoner-of-war camp in Lille. He was released in February 1920 whereupon he returned home to Östringen.

In the 1920s Julius moved to Mingolsheim and lived at Leopoldstrasse 11. He had a small business trading in agricultural products and livestock and together with his siblings he also owned and cultivated a little farmland.

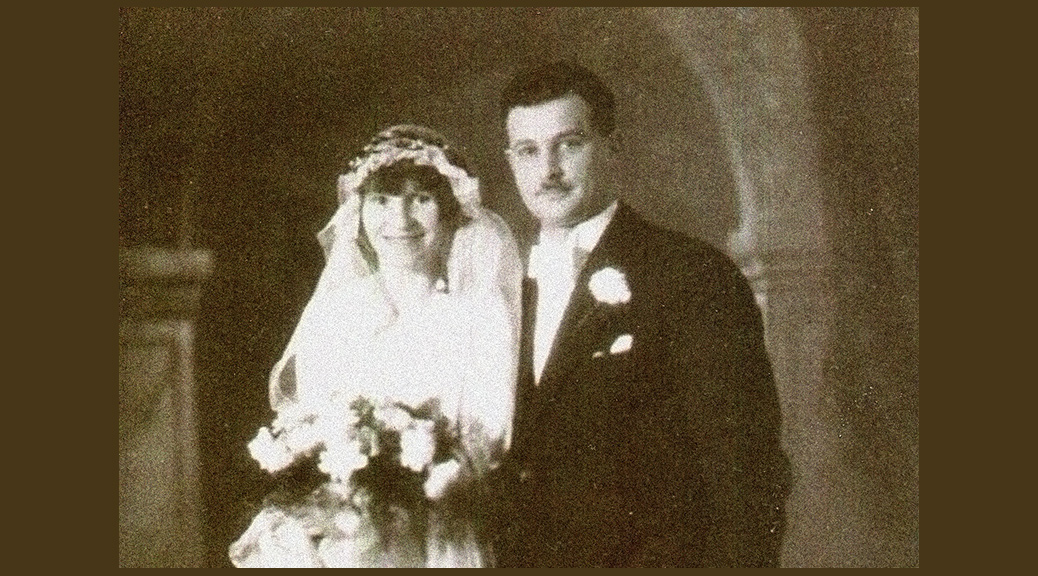

On December 19th 1930 Julius married Karolina Östreicher, the daughter of Moritz & Betty Östreicher née Fuld, his neighbours at Leopoldstraße 3. Karolina was born on November 1st 1903 and their son, Herbert, was born on March 5th 1931. Sadly, Julius’ and Karolina’s happiness was not to last long, for on March 5th 1936 (Herbert’s 5th birthday) Karolina died.

From then on, Herbert was cared for mainly by his grandmother, Betty Östreicher. On November 13th that same year Herbert’s grandfather, Moritz Östreicher, also passed away. His permit to trade in livestock had been renewed on January 24th 1921. In addition, he was authorised to trade wholesale in food and animal feed. In Mingolsheim in 1927, eleven people held similar permits, among them two more Jewish businessmen, Maier Mai and Abraham Moses. In 1933, when the National Socialist boycott actions started, overseen and fiercely propagated by the district farming community, even though Moritz did not actually lose his permission to trade, his economic situation became ever more difficult. Things then got even worse when a non-Jewish business partner, to whom he had lent substantial sums of money, went bankrupt. The financial authorities kept pushing for payment of his debts and in 1936 even threatened a foreclosure sale of his house contents. At the last minute, this action was halted because of his poor health and the fact that his daughter was terminally ill. His desperate situation almost certainly contributed to his declining health and subsequent premature death, as well as that of his daughter.

On January 15th 1936, Moritz’s son, Max, applied for permission to trade livestock – obviously he wanted to continue his father’s business. But he didn’t get official approval. As was usual at the time, the Nazi bureaucracy did not openly express their racist reasoning and instead he was told that there were already too many similar businesses in existence.

It soon became clear who really benefited from that. Early in 1937, a local butcher applied for a similar livestock trade permit. By letter of April 22nd, the mayor’s office approved his application as there was apparently a big demand for this trade and certainly no problem with over-supply. After all, Moritz Östreicher was dead, his son Max had been refused a permit and Julius Falk had had his revoked. The new applicant was reliable, had a good reputation, was knowledgeable knowledge and, of course, was Arian.

Julius Falk remarried in May 1937 and Emma (née Spiegel, from Ahlen in Münsterland) moved in with him in Leopoldstraße 11. She was the daughter of Abraham and Settchen Spielgel and was born in 1899.

Herbert Falk now lived next door with his grandmother, Betty Östreicher. As soon as he started to attend school, his teacher, Gruber, mocked him with anti-Semitic aggression. So Betty and her son, Max, started to make plans to emigrate with Herbert. Betty’s second daughter, Bertha, had already settled in the Chicago area in 1933, where she had also married and recently had a baby.

In July 1938, passports were requested for Betty, Max and Herbert and on August 22nd they got their visas for the US in Stuttgart. They planned to leave Mingolsheim on December 14th. However, on November 10th, the morning after “Kristallnacht”, SA members (Brownshirts) from another area and local party members raided their house and destroyed most of their furnishings and belongings. When the mob realised that they couldn’t burn the local synagogue because it had already been sold to Arians, they turned their attention to the nearby homes of the Falk and Östreicher families.

All the men, including Max Östreicher and Julius Falk were taken into “protective custody” and transferred to Dachau concentration camp. Literally at the last minute, Max was freed from the camp and able to leave the country as planned. Because they had sold their house and the new owners had already moved in, they were given a roof over their heads fo their last night by Franziska Moses in Bruchsaler Straße. In the early hours they left and ran to the station to catch the train to the North Sea. A few of their surviving household goods had been sent on ahead, and Betty and Max were only allowed to take with them 50 Reichsmarks each. They left Bremen on the SS “Europa” on December 16th and sailed to New York. They were saved. Once again, the National Socialists had achieved their goal of driving Jews out of Germany by depriving them of their livelihood.

Julius Falk was not able to leave Germany with his son, Herbert, mother-in-law and brother-in law. The following information helps to explain why this was:

On April 14th 1935, the district office had prohibited Julius Falk from carrying on any trade with livestock. The “Reichsbauernschaft” (National Farmers’ Association) had accused him of consistent dubious business practices. Although he still held his business license, in September he was banned from trading completely. An investigation had supposedly revealed that he did not possess the necessary good character. He had a criminal record of two cases of fraud and had also done business without a permit. He had done shady deals on numerous occasions and had had to take back cows he had sold. The district vet confirmed that he couldn’t be trusted. He had twice conned a farmer who was said not to be too bright and two further farmers had also been duped by him. The vet in nearby Stettfeld stated that Julius mostly offered cows of low value, so called “Jew’s cows”, which were not and would never be in calf and which would provide only very little milk. Finally, he had failed to take adequate precautions to prevent bovine tuberculosis. The district farmers’ agency had therefore decided to ban him from all further trade.

The accusations are so vague as to make their verification impossible. This seems to have been the intention and one there is good reason to doubt the accuracy of the information. To start with, the usual Nazi-agitation wording, reminiscent of that used in the NS hate publication ‘Stürmer’, raises suspicion. That a vet should use such wording suggests that he was providing not so much a professional opinion but more one which would better serve the purposes of the Party, which excluded any possibility of fairness with regard to Jews. Also, the Farmers’ Association was well-known for its fierce antisemitism. It’s not beyond the realms of possibility that an impressionable ‘witness’ (if he or she ever even existed) was put under pressure and forced to speak out against Julius. Furthermore, in those days a Jewish person did not have any chance of seeking assistance from a court if he had been villainized, cheated, or refused money for his service. Even sympathetic or well-meaning judges had hardly any option other than to make the complainant aware of the probable consequences of his appeal before it went on file: he would be exposed to the party’s organized mob and suffer all manner of harassment.

In 1936, Julius had his license to trade in products such hay, straw, animal feed, flour, cereals and seeds withdrawn. No formal grounds were stated and there was nothing else the young widower could live from other than the small areas of farmland he had inherited. The economic hardship was so great that he had to pawn or sell more and more of his possessions. He didn’t have the financial means to arrange his emigration.

His precarious situation is highlighted in a letter from the local banking cooperative dated January 1939. Shortly after the Östreicher family had left for the US, the Angelbachtal bank informed the Mingolsheim mayor’s office that Julius Falk had numerous outstanding accounts and bills of exchange, which were secured by mortgages on his property. The mayor was asked to ensure that Julius did not emigrate in order to escape his financial obligations. It therefore became impossible for him to sell anything else in order to buy a ticket and he was unable even to apply for a passport or travel permit.

For a short time during 1938, Julius had taken on a teenager named Manfred Messingrau as an assistant. Manfred had grown up in Leipzig with his parents and sister; his grandfather was a well-known teacher and cantor in Aschersleben. Manfred had been sent to Mingolsheim to get some training in farming. This gives the impression that he, like many other Jewish youngsters, was equipping himself for emigration to Palestine and work in a kibbutz. In May he went to Mannheim for a short while, before returning to Leipzig. In early 1939 he left Germany for Warsaw, the birth-place of his father. This is all we know about him. Descendants of his mother’s sister continue to research into his fate. The little Mingolsheim episode confirms that in 1938 Julius was still actively involved with agriculture.

About 10 days after his “Kristallnacht” arrest, Julius was released from Dachau and returned to his wife. He was therefore able to say farewell to Herbert and to have a final photograph taken together with him.

It wasn’t easy for Julius Falk to be parted from his son. In 1939, in the only one of his letters which arrived in America, he wrote: “What’s left of life if one can’t have one’s child at one’s side and watch him grow up?” But he clearly understood that at the time it was wrong for a father not to want to send his child to the safety of another country. He continued: “Now I have to console myself like so many other parents who in recent years have had to send their children away. I am confident that, thank God, dear Herbert is in good hands, is fit and well cared for and for that I will be eternally grateful.” Further evidence of how much he loved his son is to be found in the many activities he undertook with Herbert during their final months together. To this day, Herbert still has fond memories of outings to the local sulphur baths.

Because of his arrest, Julius Falk had not been able to provide some required documentation by the stated deadline and this meant that the sale of the Östreichers’ couldn’t be legally finalised. For months Julius had this to worry about as well, not least because the NS Government imposed ever stricter conditions, for instance by introducing a Reichsfluchtsteuer (exit tax) with the aim of grabbing as much of a person’s assets for itself. The house actually had such a large mortgage on it that when it was sold there was no money surplus at all, but even this was interpreted by the authorities as suspected fraud.

Despite these difficult conditions, Julius wanted to make his way in Germany and at first he was successful: he farmed his parents’ fields in Östringen, which had been left to him by his mother. In addition, he received a small but regular income thanks to his two milk cows – at least for as long as the local dairy continued to buy the milk from him. We don’t know when that arrangement came to an end.

In 1939 his unmarried elder sister, Elsa from Heidelberg, moved in with them. By that time both parents had died. A second sister, Hilda, lived in Frankfurt am Main. Their younger brother, Berthold, had been imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp since July 1938. In September he was transferred to Buchenwald, where the conditions were even more awful.

On October 22nd 1940, Julius, Emma and Elsa Falk, along with Franziska Moses, were deported from Mingolsheim. They were given just two hours to pack a suitcase and enough food for three days. They also had to hand over all their valuables and money, save for 50 Reichsmarks each, and gather at the Mingolsheim market square. Many of their neighbours witnessed what took place there: they had to climb aboard a truck, which was to take them to Bruchsal station. Reportedly, the wife of the farmers’ leader applauded loudly as the truck left. Along with all the Jews from Baden and the Pfalz they were taken by train to unoccupied southern France, where the local authorities sent them to the Camp de Gurs in the foothills of the Pyrenees.

Only four weeks later, on November 21st 1940, the order was given to sell at auction “all of Julius Israel Falk’s property”. By March 1941, every movable item had been sold. The buyers were obviously convinced that the rightful owner would never come back or be able to reclaim his property.

The people deported from Mingolsheim survived the gruesome first months in Gurs under appalling conditions. Men and women were separated from each other, families were torn apart. Like others who fell ill, Elsa Falk was later transferred to Camp de Récébédou, where she died on June 30th 1942. In July and August of that year, Camp de Gurs was cleared. Almost everybody there was transported by train via Drancy (near Paris) to one of the extermination camps in the East. Julius Falk was taken to Auschwitz on August 14th on transport No.19. If he was not immediately killed in the gas chambers, he probably died some weeks later due to malnutrition and exhaustion from inhuman treatment and forced labour. His actual date of death is unknown. On August 25th 1942, his wife, Emma, was taken from Gurs to Drancy. She left this transfer station on September 2nd on transport No.27 and was probably killed in one of the Auschwitz gas chambers immediately after arrival.

Julius’s sister, Hilda, was deported from Frankfurt to the Lodz Ghetto on October 20th 1941; she died either there or in the Chelmno gas chambers.

The brother, Berthold, had been released from Buchenwald in February 1940 and had then moved in with his sister in Frankfurt. Like her, he was also deported to Lodz and died wither there or in Chelmno on May 4th 1942.

Herbert Falk was the only member of his family to survive the Nazi atrocities. He lived in the area near Chicago, along with his grandmother, Betty, who helped out at a local dairy farm. Betty died at the age of just 63 in 1943, thereafter Herbert’s uncle Max took him in. Max also worked on the farm. Without any formal qualifications and with very little English he found it hard to get a well-paid job. He married quite late but never really gained a foothold in America.

As an orphan Hebert joined the Military at an early age. Later, he established his own business. He married and had four children, four grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In 1977, along with his wife he visited Mingolsheim again for the first time. Throughout his life he has kept in contact with his former school friend, Ernst Willhauck. In 1982 he even attended the annual reunion of the class which he had had to leave after just 6 months. He placed his handicraft business in the hands of his son many years ago. Sadly, Herbert no longer enjoys the best of health. Nevertheless he remains interested in news from his former home and is pleased about all the efforts which are being made here to ensure that those who were driven away and killed will never be forgotten. He is emphatic in his approval and support of the laying of Stolpersteine.

Hans-Georg Schmitz, Translation Peter Silver